Racial Disparities in Healthcare: A Call to Action

Reflecting on the significant events of 2020, most notably, heightened racial unrest and the unequal impact of COVID-19, we have a unique and time-sensitive opportunity to address the reality that racial disparities exist in our country. Racial disparities permeate across many aspects of American life, but are particularly stark in healthcare; disparities in diagnoses and treatments contribute to poorer health outcomes. Black Americans are the most impacted by these healthcare inequities and continue to experience worse health outcomes than white Americans. Across the board, these inequities manifest into significant economic losses that impact a wide range of health system, business and government stakeholders.

COVID-19 outcomes have highlighted the need to address these long-standing inequities within the healthcare system, as Black Americans have been disproportionately affected. As of December 2020, the CDC reports that Black Americans are almost one and a half times more likely to contract COVID-19 and over two and a half times more likely to die from the disease. This is due to a variety of factors including, but not limited to, the lack of quality care and delayed treatment. President Joe Biden has established a COVID-19 equity task force to address the issues minorities faced throughout the pandemic. This task force is led by Dr. Marcella Nunez Smith, one of the nation’s experts on disparities in healthcare access. The creation of this task force and nomination of Dr. Nunez-Smith demonstrates a national shift in attention to health disparities highlighted by COVID-19.

At HealthScape Advisors, we are investing more dedicated time and energy into understanding this multi-faceted issue in order to best educate and support our health plan clients to be a part of the solution. Addressing racial disparities and health equity will be a focus of our firm in 2021 and beyond.

In this Executive Briefing, we will define racial disparities, describe the impact on the healthcare industry and provide recommendations for health plans to help address the issue. Although there are racial disparities in care and outcomes across all underrepresented populations, our focus for this briefing will be on disparities between the Black and white population in the U.S.; however, our recommendations for health plans are relevant for all racial groups.

WE BELIEVE TACKLING RACIAL INEQUITIES IN HEALTH SHOULD BE A MAJOR PRIORITY FOR HEALTHCARE ORGANIZATIONS. RACIAL DISPARITIES ARE NOT NEW BUT MOMENTUM FROM RECENT EVENTS LEAVE US WITH AN OPPORTUNITY TO LEAD DIFFERENTLY.

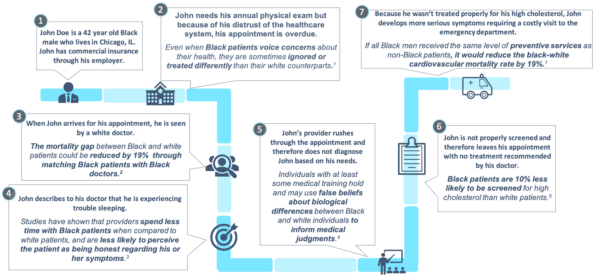

Illustration of the Implicit Bias Impact

There are two leading contributors to racial disparities in healthcare: social determinants of health (SDOH) and implicit bias. Social determinants of health are conditions in the places where people live, learn, work and play that affect a wide range of health and quality of life risks and outcomes.

Racial disparities present in SDOH can include social inequalities, culturally competent care components, and disparate access to healthcare services, among others. Implicit bias, also known as unconscious bias, refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions and decisions in an unconscious manner. Implicit bias in healthcare can include provider bias as it relates to diagnosis and treatment as well as policy development and execution. Together, SDOH and implicit bias are inextricably linked to poor health outcomes among minority populations.

The healthcare industry has thus far recognized and publicly developed and announced programs addressing SDOH. Many health plans, especially those serving more underserved populations, have successfully implemented point solutions that address specific social needs such as economic stability, access to food, and community and social factors. As highlighted in our recent Executive Briefing Social Determinants of Health: Driving Sustainable Healthcare Value as a Convener, the interconnectedness of life demonstrates why providing holistic healthcare that delivers long-term results is hindered by a primarily clinical approach. Further, the current COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the need for a convener to address social barriers for access to care and the impact of non-clinical factors on healthcare access, quality and outcomes.

However, even when accounting for social, environmental and cultural factors, racial disparities are still prevalent in healthcare; this demonstrates evidence of implicit bias across all points of healthcare delivery. Because it operates unconsciously and unintentionally, implicit bias is difficult to understand and identify and even harder to change. Implicit bias and mistrust in the healthcare system is an especially deep-rooted issue within the Black American population. The primary contributors to Black American distrust include lower rates of healthcare coverage and racial stereotyping based on false beliefs. Harvard historian Evelynn Hammonds describes the disparity simply: “[there] has never been any period in American history where the health of blacks was equal to that of whites. Disparity is built into the system.”

In Exhibit 1 below, we have created an example of how provider-patient implicit bias can impact health outcomes through an illustrative healthcare journey of John, a 42-year-old Black man. John is in good health, lives in an affluent area in Chicago and has a commercial health insurance plan through his employer. This is pertinent to note because this means John has no issues with either healthcare access or healthcare payment in this scenario. Removing these factors (largely the factors associated with SDOH) provides a scenario with one glaring variable—race.

Exhibit 1: Illustration of the Implicit Bias Impact

Notes: (1) New York Times, Bad Medicine: The Harm That Comes From Racism, January 2020; (2) NEJM, Diagnosing and Treating Systemic Racism, July 2020; (3) The Hill, Black Americans don’t trust our healthcare system — here’s why, October 2017; (4) PNAS, Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites, April 2016; (5) Forbes, Why Health Care Is Different If You’re Black, Latino Or Poor, March 2015.

Defining Racial Disparities in Healthcare

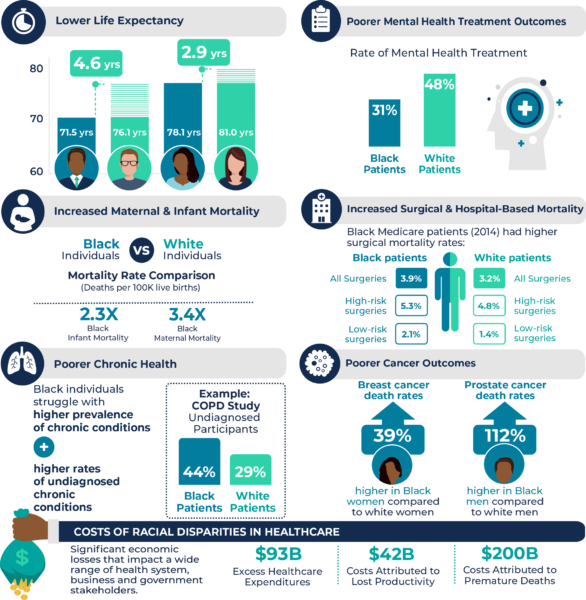

Black individuals do not receive the same quality of care as their white counterparts. This contributes to “racial and ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention”. Stark evidence of this is evident in the myriad of poorer health outcomes for the Black population when compared to the white population, including maternal and infant mortality rates and rates / outcomes of diabetes and cancer. Poorer health outcomes not only affect the Black population but also limit quality of care improvements for the broader population, contributing to unnecessary medical costs. As the U.S. population becomes more diverse, it will be increasingly important to recognize and address these issues.

Exhibit 2: The Consequences of Racial Disparities in Healthcare

Health Plan Opportunities to Address Racial Disparities in Healthcare

There are numerous health plan-led SDOH initiatives to mitigate poor health outcomes resulting from racial disparities. Although effective and meaningful, SDOH can no longer be the sole focus as implicit biases continue to affect health outcomes of the Black population.

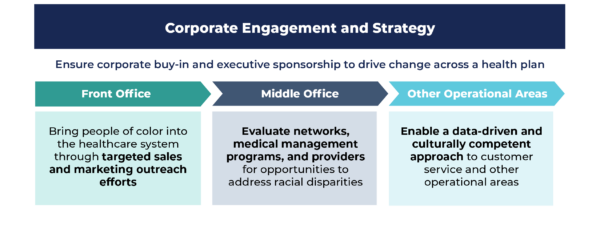

As health plans consider strategies to address racial disparities in healthcare, we encourage leaders to begin by reevaluating their company strategies and core operations while leveraging their existing community investments, such as foundations. HealthScape has identified four main opportunity areas, including corporate enagement and strategy, front office, middle office and other operational areas.

Although this paper has focused on disparities between Black and white individuals, the solutions and examples identified in the following section can be applied to all racial groups.

Corporate Engagement and Strategy:

is a foundational starting point, as executive leadership and commitment are critical to driving accountability and meaningful change across the organization. Designating a Chief Equity Officer or Equity Council of executives and leaders can help ensure critical steps, such as an operational current state assessment, bias training implementation and identification of potential community partnerships, are given the necessary resources and prominence.

For example, Tufts Health Plan launched its annual Unconscious Bias Day in 2019. This annual event pushes employees to recognize unconscious bias and arms them with techniques to address and mitigate occurrences within the workplace. It is important to acknowledge that while many health plans have internal strategies to realize a more diverse, equitable and inclusive employee base, we encourage our clients to equally invest in addressing inequities in their communities that affect their members. Additionally, executive leadership must consider methodologies for defining the return on investment of programs that address racial disparities, as they ultimately must address broader goals of improving health outcomes and reducing costs. Thus, a holistic corporate strategy should not only cater to a core mission of reducing racial inequalities in healthcare but also remain financially sustainable and sensible.

Within health plan operations, we encourage plans to identify opportunities to improve inequities across front, middle and other operational activities. Through targeted outreach efforts, plans can bring Black individuals into the healthcare system and engage them in a way that ensures future health plan and provider interactions are culturally competent.

Marketing, Sales and Product:

Plans can help address racial disparities by instituting multicultural marketing departments and connecting them to local communities. Leveraging a multicultural marketing department will allow health plan staff to better understand and develop communications, programs and events that target underserved populations. Additionally, there are opportunities to create connections with community leaders and community centers (e.g., churches, organizations) for prevention outreach and provision of care resources as underserved populations continue to face declining outcomes. Utilizing advertising budgets and funds from operational areas gives plans the flexibility to increase resources and leadership focus on enhancements to current outreach.

For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts has developed a Multicultural Market Ambassador Program that enables it to work with clients to target underserved populations and utilize data analytics to develop culturally competent communications, programs and events. Program ambassadors also attend community events to help reach more members and educate individuals on healthcare needs.

Network and Care Management:

Within middle office functions, health plans have an opportunity to address the critical issues of care, access and quality through provider network efforts and more informed medical management programs and benefit design. Plans can also design provider reimbursement incentive models that promote equitable care. These reimbursement models should include factors to measure racial inequalities as a metric in the overall quality rating of providers. Adding a racial disparities component to existing quality standards will allow plans to promote providers that have demonstrated a high level of cultural competency and lack of racial bias.

For example, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois (BCBCIL) launched two health equity programs to address racial disparities in healthcare by improving health outcomes of minority patients and increasing diversity among its medical professionals. Supported by $100 million in funding to be provided to ~10 participating hospitals and health systems, BCBCIL launched the Health Equity Quality Incentive Program to address systematic racism and discrimination that impact the health of minorities. The Program’s immediate objective is to support hospitals serving the highest concentrations of BCBSIL members in Illinois communities who are most at risk of contracting COVID-19. The plan is also piloting the Institute for Physician Diversity to achieve greater racial and ethnic diversity in the provider workforce. This program will accelerate the recruitment of underrepresented medical professionals and emphasize the importance of continual implicit bias education for medical professionals and senior leadership.

A partnership between CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield and Mamatoto Village is another example of a middle office opportunity that can address the poor health outcomes in the Black community. Mamatoto Village is a non-profit organization devoted to 1) creating career pathways for Black women in the field of public health and human services and 2) providing accessible perinatal support services designed to empower women with the necessary tools to make the most informed decisions in their maternity care, parenting and lives. The partnership provides support for Black women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period for Medicaid members. As a result of this partnership, mothers who received prenatal and labor support had newborns with an average birth weight of 6.98 lbs. compared with 6.07 lbs. for post-birth program entrants. This collaboration is a great example of a targeted program that helps improve health outcomes for Black members and reduces racial disparities.

Another example of a potential health plan partner is the platform HUED, which is designed to address health disparities highlighted by improper treatment and misdiagnoses received by Black and Latinx patients. This platform assists patients in finding health and medical professionals of color, increasing quality of care and access while aiming to reduce the communities’ distrust in the healthcare system. By connecting patients with culturally competent medical professionals, HUED aims to improve health outcomes for both the Black and Latinx populations. Plans can utilize the HUED platform to connect their members to in-network providers of color, mitigating implicit biases experienced by the member and increasing the member’s trust in the healthcare system. Working with an organization like HUED that has an existing database of health and medical professionals of color can help plans ensure they are connecting their members with providers best suited to fit their healthcare needs.

Customer Service and Core Operations:

Finally, within their other operational areas (back office), plans need to consider the importance of a data-driven strategy for identifying, measuring and addressing racial disparities.

For example, UnitedHealthcare, the health benefits business of UnitedHealth Group, voluntarily collects race, ethnicity, and language (REL) data to help provide more personalized care. This data allows the plan to detect and reduce disparities in care, ensure members receive appropriate benefits, and provide members more culturally and linguistically appropriate programs and services.

Additionally, data collection and analytics processes may be biased in either the data that is not collected (e.g., race, ethnicity, and language data) or in the ways that algorithms are designed (e.g., basing risk scores solely on healthcare spending).

Gateway Health, for example, recently uncovered a racial bias in a nationally recognized risk score model, finding differences in healthcare costs for Black and white individuals with the same clinical risk score. To address this, Gateway’s Research and Development team applied data on community-level, non-clinical barriers (e.g., food and housing insecurity, environmental risk, structural poverty) to the clinical risk score to produce a Member Centric Index Score, or MCI. MCI scores were shown to be higher for Black individuals than for white individuals, allowing Gateway to compensate for the bias in the model.

Additionally, plans should consider holding regular and new-hire implicit bias and cultural competency training sessions for customer service representatives. Implicit bias trainings challenge employees to recognize their own biases and become more aware of their behavior when interacting with members. Cultural competency training provides further context on the challenges non-white members face and the unique needs of specific member demographics. Principles of cultural competency should also be applied to development of member onboarding materials (including proper representation in pictures and graphics), content directed towards non-white members, and resources referencing racial disparities in healthcare.

Whether pursuing these activities independently via existing programs or foundations or seeking partnerships, plans can significantly influence solutions to address racial disparities in healthcare. Once the portfolio of initiatives to address racial disparities is identified, each area of the operational chain can contribute in multiple and meaningful ways.

Racial disparities in healthcare are stark, driven by complex systemic issues as well as implicit bias. As the country continues to grapple with inequities highlighted by the pandemic and Black Lives Matter movement, it is important that we act now to address these issues. Health plans, in particular, are well-positioned to effect change by prioritizing efforts to identify implicit bias and structural racism within their organizations and develop measurable strategies to address.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

INVITATION FROM HEALTHSCAPE

HealthScape invites health plans to discuss their priorities and collaborate with us on strategies and solutions to reduce racial disparities in healthcare. Please contact Tej Shah and Jesse Owdom to schedule time for a discussion tailored towards your local community.